Mayor Jim Boult flying high on the Kawarau bungy as we came out of COVID lockdown. The only direction from up is…

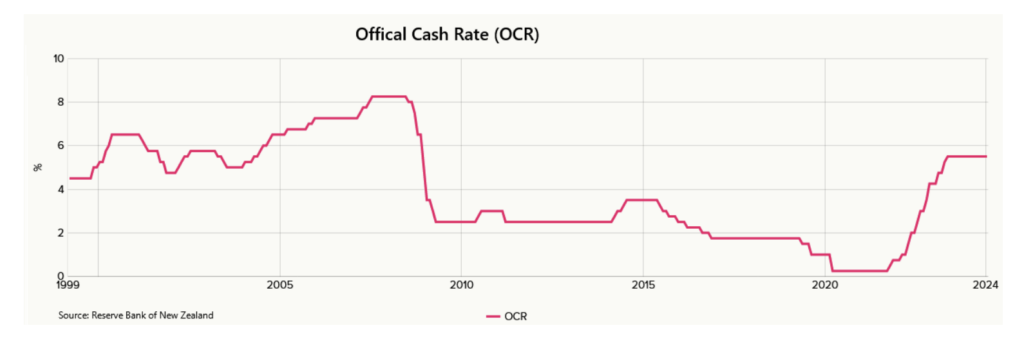

Industry is pretty close to begging the Reserve Bank to use its blunt instrument of the official cash rate (OCR) next week and decrease the rate to improve business conditions. It never ceases to amaze me we largely control the state of our economy by a single lever – the OCR. That’s probably why I wrote about inflation and the OCR in 2021 Inflation-Interest Rates and 2022 Manifest Inflation.

The OCR is the rate the central bank charges merchant banks when they borrow money. Those merchant banks lend money to people and businesses, and the interest rate at which they lend is affected by the interest rate charged on the money they are borrowing from the central bank. In other words, as the OCR rises, interest rates rise on loans, including mortgages.

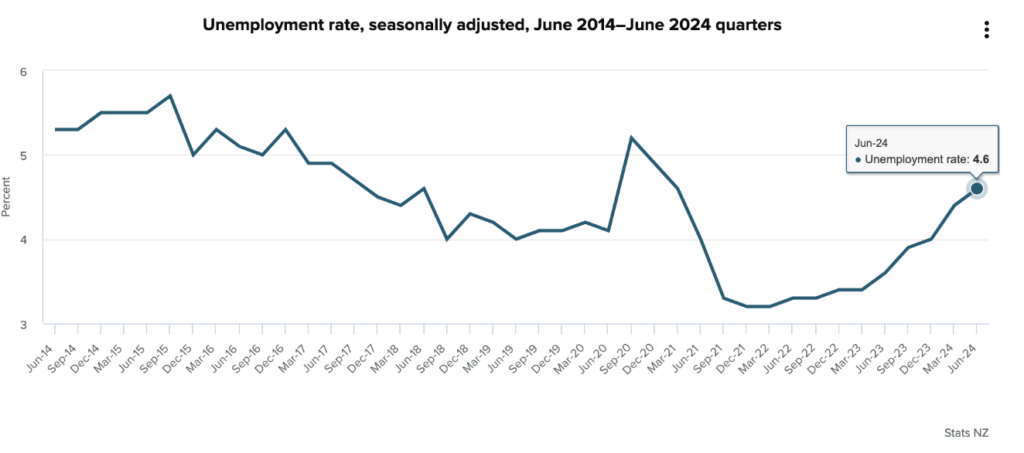

There was a lot of surprise expressed this week about how we manage the overheated economy through putting people out of jobs via the OCR – the Reserve Bank raises the OCR, increases the cost of borrowing money, then businesses can’t afford to employ as many staff or can’t afford to operate. Over the last year, unemployment in New Zealand rose to 4.6% by 33,000 to 143,000 people.

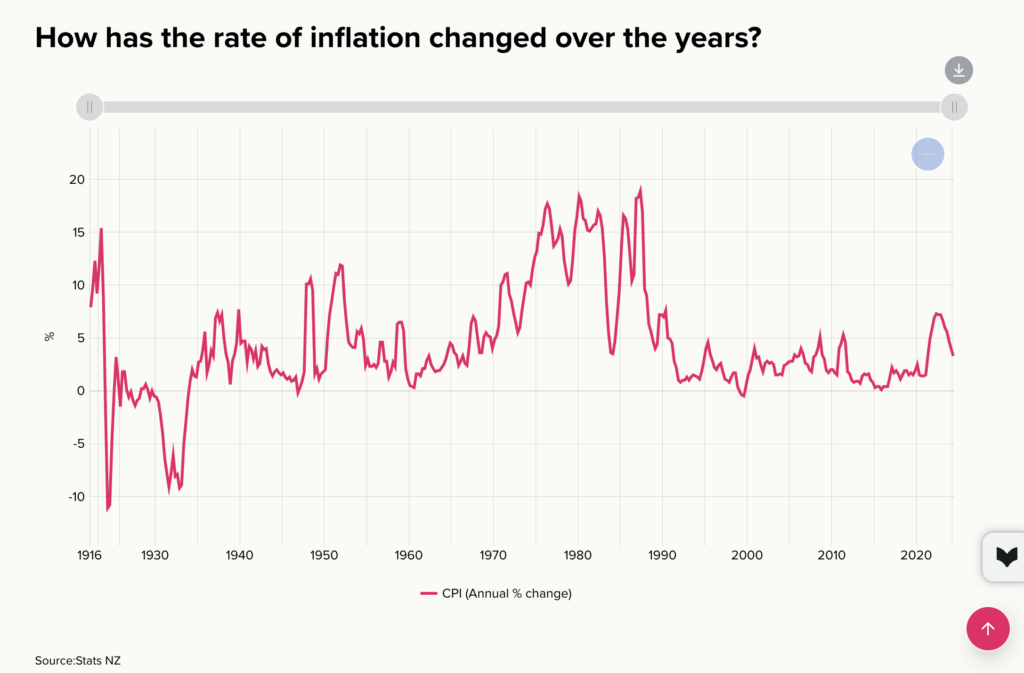

In 2022, the Reserve Bank started increasing the OCR in response to rising inflation. Inflation took off from a low of 1.4% in December 2020 following on from a nearly twenties years of stability between 1% and 3%. Inflation peaked at a twenty year high of 7.3% in September 2022. One of the Reserve Banks roles is to keep inflation low and stable, between 1% and 3%. The Bank is also required to accomplish this task without unnecessary instability in output, interest rates and the exchange rate.

The Bank was given this inflation-controlling role in the Reserve Bank Act of 1989, during New Zealand’s huge overhaul of how our country was run (if you want a synopsis of the era from the Muldoon government through the Lange-Douglas government, have a listen to The Spinoff’s Juggernaut podcast).

There was a general drive to control inflation in western economies in the late 1980s and early 1990s. New Zealand saw inflation peak at 17-18% a number of times between 1976 and 1987. The Lange-Douglas government pioneered the monetary policy step of a specific target band for inflation as a result. However, this style of inflation targeting is now used by a number of significant economies, including Canada, the United Kingdom, Norway, Poland, South Africa, Sweden, Australia and the Eurozone.

It’s in the interests of New Zealanders that the Reserve Bank controls inflation. High inflation means people can’t afford to buy what they previously could afford. They can’t afford to pay their mortgages. There are flow-on effects – people and organisations don’t save or invest in the future because they aren’t sure what value their money will have in the future. I remember this vividly from the 1970s: should I buy a new red Raleigh bicycle this month or next month? The answer was obvious, buy it this month because next month it might cost more than the amount of money I had saved.

Banks want to keep inflation under control because very rapid inflation, ‘hyperinflation’, is an extremely scary prospect. In 1922-1924 Germany, inflation was so high that employers paid workers on the hour and people rushed spend the cash before it lost value. Children made kites from worthless banknotes. Mothers lit fires with cash because it was cheaper than buying kindling. Note-printers could not keep up with demand for notes of ever-increasing denomination. Unemployment skyrocketed, people went hungry, the government lost revenue because businesses delayed paying tax to reduce the cost of the expense; the economy began to collapse. Then there was a World War (okay, that’s a bit of a simplification).

In the year ended April 2007, Zimbabwe reportedly had inflation of around 3730%. I remember Chris’s Zimbabwean colleague telling us how, when he’d gone home to Harare for a visit, the price of a can of coke increased between when he took it off the shelf and when he paid for it!

We don’t, and haven’t, had hyperinflation here. But how did New Zealand end up with rapidly rising inflation 2021 to 2022 and therefore raise the OCR?

The normal reasons for inflation are:

- Too much money is available to purchase too few goods and services.

- Demand in the economy is outpacing supply – this generally results from a buoyant economy causing widespread shortages of labour and materials, and people can charge higher prices for the same goods or services.

- Inflation can also be caused by a rise in the prices of imported commodities, such as oil. However, this sort of inflation is usually more transient, and therefore less crucial, than the structural inflation caused by an over-supply of money.

New Zealand ‘caught’ inflation because of all the above factors:

- During COVID, the government used quantitative easing to print $60 billion because it was terrified COVID would result in unemployment, i.e. they substantially increased the supply of money.

- During COVID, the Reserve Bank decreased the OCR to stimulate the economy because it was scared NZ might go into a recession.

- During and post-COVID, people started spending all the money they didn’t spend while locked down and locked in New Zealand.

- The Ukraine war increased prices globally for important commodities, including oil and wheat.

New Zealand wasn’t the only country to print money; it was in a huge cohort of money printers. The world had ceased to believe printing money would result in inflation, because inflation rates had stayed so low for so long. In fact, shortly before the Reserve Bank started raising the OCR, the country still thought we were about to enter deflation, the opposite evil from hyperinflation. We were warned interest rates might go negative (that was a brain-teaser – what do you do if the bank charges you to hold onto your money?). We’d stopped believing the long-term basic economic principle of supply and demand: increasing supply of Z beyond levels of demand for Z means Z becomes worth less. In this case, Z was money.

So, New Zealand printed money and dropped the OCR to keep people employed in 2020-2022. As a result, tens of thousands of people now have to lose the jobs they kept in 2020-2022 in order to make up for the fact they got to keep those jobs. Blunt instrument indeed! Is more finesse required or are cyclical rises and falls our forever destiny?

Discover more from Jane Shearer

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.