Studying Disasters

How many elk are left around Jasper township in Alberta? Very few because massive wildfires devastated the forest around the town last week and burned one third of the buildings in Jasper to the ground.

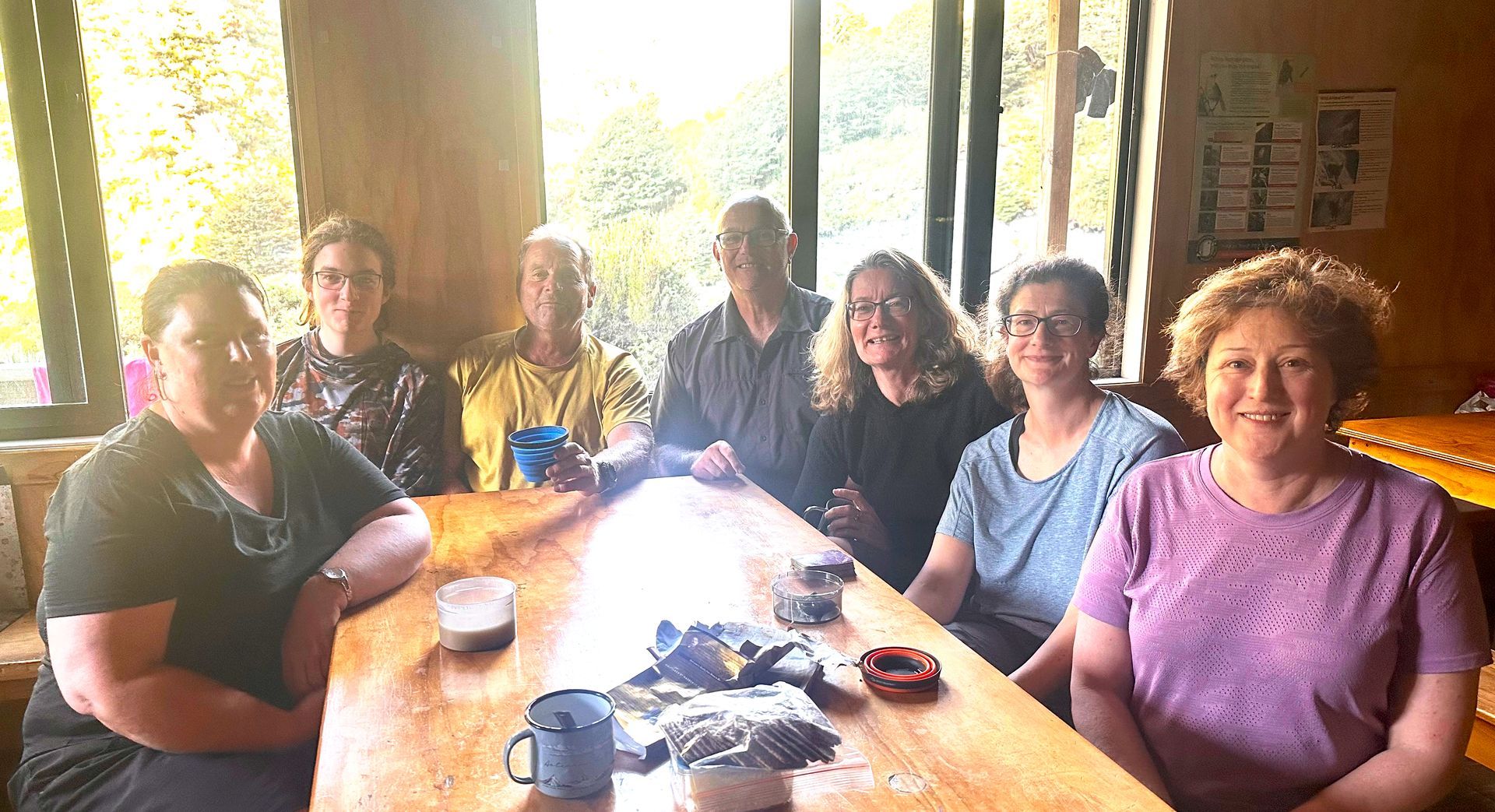

I was more upset than I expected to hear the news about Jasper. It's a place I will always hold special. I lived there for over 6 months in 1987, working first as a liftie at the Marmot Basin ski hill and then as a waitress in town during the summer. Jasper was where I learned to mountain bike, in the forest on the glacial plateau above the town (including meeting a bear at close quarters). I went hiking in the forests and up mountains every weekend for three months in a row. I learned how to be happy again after losing my way during an exceptionally unenjoyable last year of a BScHons degree in geology.

Jasper is a place people visit and then want to stay – my friend Heather, whose townhouse has escaped last week's fire (although she still can't go home and more fires are on their way) went to Jasper to work at Marmot in 1985 and has never left. While Jasper is a tourist mecca, it doesn't have the superficial glitz of Banff, or Lake Louise – it feels like a home.

Having lived through the Canterbury earthquakes, I can see the start of the process for Jasperites...the very start is Jasper dropping out of the news. Last week it headlined, this week Jasper is subsumed by the Olympics. Next come the declarations – we will rebuild! It will be great again! Soon!

Jasper may well be great again, but it won't be great for far longer than people expect. And the now-believed-in threat of wildfire will hang over people's heads for far longer than they would prefer. If fire is anything like earthquakes, you believe in wildfire as a theoretical concept before you experience it, then believe in it viscerally once it has happened to you.

New Zealand doesn't worry enough about fires, yet. Neighbour Australia, does, but we have yet to learn much from them about how to prevent and manage fires, particularly in relation to our infrastructure. Sprinkler systems, clearing vegetation away from houses, keeping gutters empty of leaf litter, garden plants that don't burn easily, low combustible housing material, simple roof structures that don't hold burning embers...

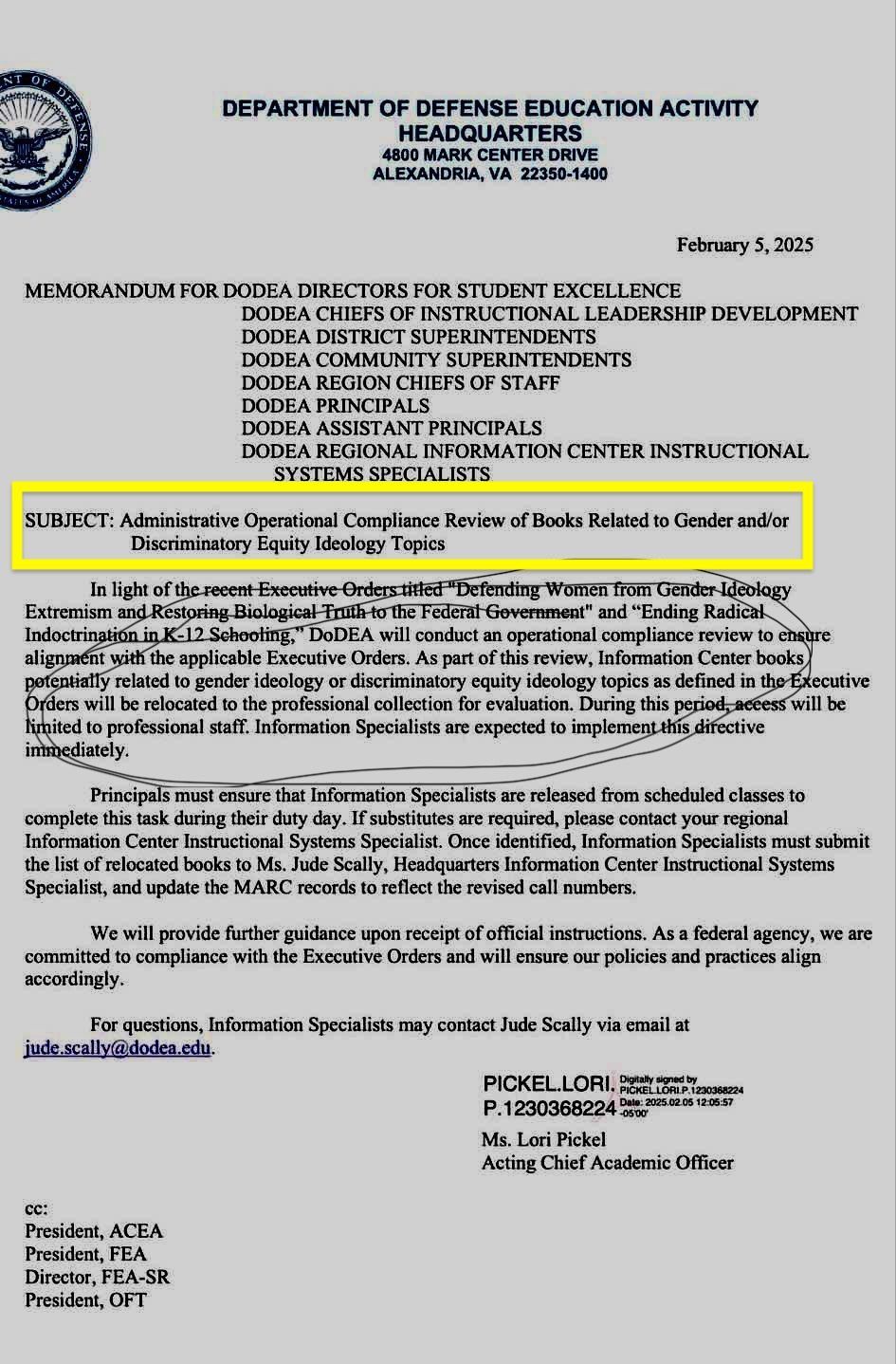

Do we need to know more to avoid fire hazard? This is a perennial question, also in the news this week. Not so much about fires specifically, but do we need to know more in general? Headlinesincluded the loss of geoscientists from GNS Science and a general decline in PhD graduates. Cuts to Scion, which has the biggest cohort of fire researchers, are old news - from May. The article about PhD graduates says, "Declining PhD student numbers are a warning sign for NZ’s future knowledge economy...This is not only about economic growth. [Declining numbers break the] implicit social contract promising improved living standards, better public services and support for vital societal outcomes."

Is there really an implicit social contract associated with PhD graduates? If we have fewer people with PhDs, will we have worse living standards, worse public service and worse social outcomes? One senior university academic said, in reference to the lack of PhD graduates, "We want a high value-added economy, a just society and a healthy environment. We are unlikely to get them." I find myself highly sceptical. More PhDs may come as a result of being a better-off society, but over three decades working in the research and innovation sector has not left me convinced our society is always better off as a result of more research. For a start, we have been on the 'knowledge economy' bent for thirty years – if we haven't made a difference in that time, maybe we are doing the wrong thing? Or maybe it isn't such a tractable problem?

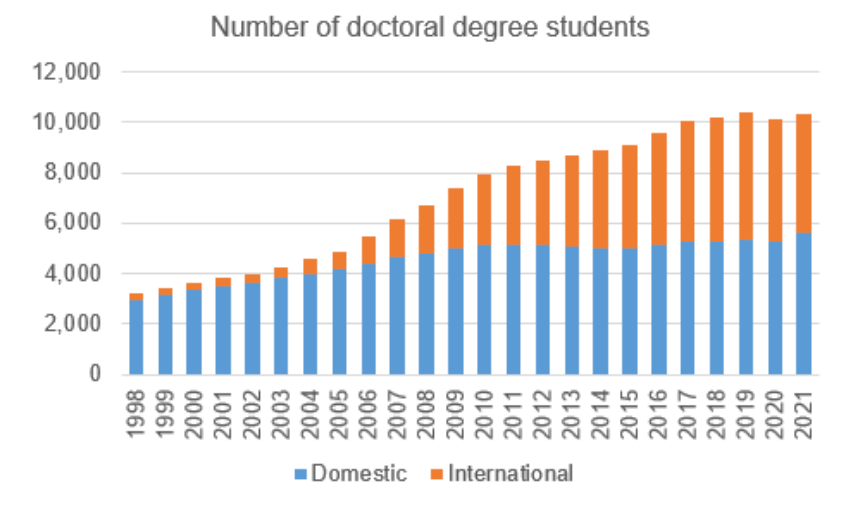

We have seen increasing numbers of students enrolled in PhDs in New Zealand in the last two decades, as well as increasing numbers of students completing PhD degrees. In fact, we have got better at getting students through to graduation – in 2021, there were 3.3x more PhD students than in 1998, but 4x as many graduates. We have increased the proportion of our population graduating with PhDs - from 121 PhDs per million people each year to 140 (that's the domestic graduands). We have markedly increased numbers of graduating foreign students, from around 20 to nearly 900 a year. Have any of these driven an added value economy, or better social outcomes? Apparently not, because the people claiming we need lots more PhD graduates are also bemoaning the state of our economy and our society.

So I ask again, 'Do we need to know more in order to improve matters?' Is a lack of added value in our economy, or social issues, the result of not knowing enough? Or is it more about not doing what we already know, or what someone else knows and would be happy to tell us about? The question of do we need to know more is a bigger question than I can tackle in one blog, or ten, but let's have a think about the fire exemplar.

There have been several very destructive/disruptive fires in the last five years in New Zealand – two in the Christchurch Port Hills, one west of Nelson, several around Lake Pukaki including one that destroyed a significant part of Ohau village. So we know New Zealand experiences wildfires, particularly in pine forests. We also know there are likely to be more fires - climate science (yes, we do sometimes need scientists) tells us there will be warmer temperatures, lower humidity, more severe droughts and stronger winds over time, and all these factors will lead to more high fire-risk days. However, the Fire Service knows from experience that most New Zealand fires are caused by people (as opposed to lightning, although there could also be more thunderstorms and lightning). So knowing more about fires isn't going to make a significant difference to fires starting. What we need to do is change people's behaviour, because people light fires.

Do we need more PhD graduates to do research to figure out how to change behaviour? I would say, in general, "No." If you take climate change, we know lots about how the climate is changing and why, and what we could do about it, but there's not much evidence of people changing their behaviour to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Will more research lead to more behaviour change? Will more facts get people to act? There's little evidence more facts drive action. And, without a doubt, getting people to change behaviour is hard.

When individual humans have to do a hard thing, they often avoid it – clean the toilet rather than study for an exam, for example. Does society mirror that behaviour? When we have to do a hard societal thing, do we avoid it? Society says, let's do some research rather than trying to actually do something. We must need more PhDs, because they are the people that do research.

Over my time working with researchers, I have discovered society already knows plenty about many topics. In a lot of cases, we know far more than we can or do enact. I would hypothesise the research community engaged in the 'business' of research want their business to stay viable and their jobs to continue to exist. They have to justify their own existence...of course researchers and academics want there to be more PhDs.

However, if we don't want more fires burning more houses, we need to do. We need to reduce burnability of our vegetation and infrastructure - we know how and, if we don't, the Ozzies know. We need to reduce our risky burning practices – the Fire Service and local councils know plenty about those and continually ask us to act. We need action more than we need research. We don't need more Jaspers.

Get new content delivered

directly to your inbox.

Latest Posts

© Jane Shearer 2020-2023. All rights reserved.

blogger

traveller